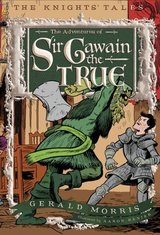

The adventures of Sir Gawain the True (The Knights' Tales, book 3) by Gerald Morris, illustrations by Aaron RenierHoughton Mifflin, 2011As a member of King Arthur's court, Sir Gawain is expected to be courteous and honourable. Unfortunately, despite his faultless record in tournaments, Sir Gawain has not quite been living up to expectations. When the mysterious Green Knight shows up at court during Christmas celebrations, Sir Gawain finds himself avowed to him and must keep his word despite the fact that it appears to mean certain death. This is the third book in Gerald Morris' The knights' tales series, although it is the first one that I have had the pleasure to read. Based on the 14th-century poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, The adventures of Sir Gawain the True makes the tale easily understandable to young students, which is not a characteristic of the original if I recall my university English courses correctly. The core of the classic story is kept - the Green Knight's challenge, the woman with her sash, the magic - and the addition of modern humor and charming illustrations certainly accentuate its entertainment value. I got a kick out of King Arthur as portrayed by Morris: he is determined to have his knights behave honourably and is very patient with them, but is occasionally exasperated. His reactions to his knights' lack of courtesy were often humourous, and his acknowledgments of improvement act as subtle cues to the reader that appropriate behaviour was displayed. After all, adventure aside, many Arthurian tales have morals and lessons within them and this version is no different. However, I didn't feel bonked over the head with a moral, and certainly Sir Gawain wasn't perfect from the beginning but manifested thoughtful and gradual change throughout the story. The tale itself is a lot of fun, with dwarves, reclusive lords, and jousting all coming into play. Morris' descriptions of period vocabulary, such as damsel and vow, are provided in the text in such a way that they provide information, history, and humour without really bringing the reader out of the story. As a fan of both language and history, I certainly appreciated his incorporation of both into the narrative. I am hesitant to discuss Aaron Renier's illustrations very much because I read an electronic galley on a Kindle and some of the drawings were split into two, which certainly detracted from my enjoyment of them. However, I did like what I saw despite the fact that Renier drew the knights and King Arthur as older than I envisioned them in my head, which took me aback a bit. That is my only critique (which should be taken with a grain of salt as ages and appearances were never discussed in the text) as the style and content of the illustrations were delightful. Morris managed to pack a legendary tale into a little over 100 pages which in itself takes great skill, to say nothing of the humour and charm of the text and illustrations. Although I've not read the previous two installments of this series, I will be seeking them out and looking forward to get my hands on them as well as any future books in The knights' tales series. **Electronic galley provided by publisher via netGalley.

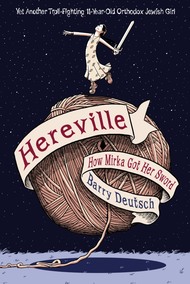

Hereville: how Mirka got her sword by Barry Deutsch

Amulet Books, 2010

Mirka wants to be a dragonslayer, but that profession doesn't exactly jive with her Orthodox Jewish upbringing. One day on her way to school, Mirka comes across a spectacular building with a woman floating in the front yard. When she tells her sisters and brother, they don't believe her so she finds the building again and picks a giant grape. Although the grape doesn't bite her, the giant pig who now follows her around might! How can she possibly get rid of it?

This graphic novel is a whole lot of fun, and I really appreciated how her religion and lifestyle played a large yet not oppressive role. Mirka's Yiddish sayings are defined at the bottom of the page, her family's beliefs are shown and explained clearly, and the conflict between her dream to be a dragonslayer and her family's beliefs was made evident. In fact, the tagline on the cover of the book really captures the sentiment throughout: "Yet another troll-fighting 11-year-old Orthodox Jewish girl." What's not to love about that?

The drawings themselves are line drawings with black ink, greys, and apart from the night-time scenes in grey-blues, the only colours are beige and an orange shade. I enjoyed Deutsch's style, which is fairly simple but with lots of expression and movement. There is a wide variety of panel layouts throughout, but they would be easy to follow and understand for even those who are new to graphic novels. I particularly adored how he drew the troll, and appreciated the back matter in which Deutsch showed how many iterations of the troll he went through before deciding on the final design.

Hereville should hold great appeal for upper elementary or middle grade students who like fantasy, or fans of graphic novels with strong female protagonists like Rapunzel's Revenge.

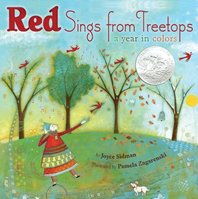

Red sings from treetops: a year in colors by Joyce Sidman, illustrated by Pamela Zagarenski

Houghton Mifflin, 2009

As a rule, I am not a lover of poetry. The only book of poetry I remember enjoying as a child is Shel Silverstein's Where the sidewalk ends due to its wit, creativity, and occasional weirdness, which fails to explain why I attempted to slog through Sir Walter Scott's epic The Lady of the Lake a few years later. In between, my grade 9 English teacher's apparent obsession with The cremation of Sam McGee by Robert Service drove me batty - there is something about the rhythm and rhyme that I didn't like - and I haven't read that blasted poem since. The thing is, if there were poetry books like Red sings from treetops when I was young, I would probably not be so averse to the genre.

Sidman essentially weaves a tale of the colours of the seasons in a narrative told in verse. There is a sequential nature to the poems as later poems tie back to earlier ones: poems about white all describe it as a sound, and poems about green follow its prevalence throughout the seasons. This flow of the poems ties in nicely with the flow of the seasons and as a group as well as individually, the poems are lovely. There is no set rhyming scheme, length, or rhythm, so the poems vary but none are more than 10-12 lines.

Zagarenski's illustrations are stunning. They are a combination of mixed media paintings on wood and computer illustration, and are magical. All the people and animals who make their way through the seasons wear crowns, even the snowman. I find it difficult to describe Zagarenski's style here, as she combines patterns and textures and pasted newsprint in a way I have never seen before. It certainly lends an air of fantasy to the poems, and I am curious if she uses the same techniques in other books.

Lovely to read and beautiful to look at.

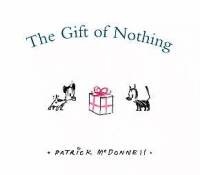

The gift of nothing by Patrick McDonnell

Little, Brown, 2005

Mooch the cat has decided to give a gift to his best friend, Earl the dog. However, Earl already has everything a dog could possibly want so Mooch decides to give him nothing. Problem is, Mooch can't seem to locate nothing since everywhere he looks, there is something. Will Mooch find it?

I don't recall reading any of McDonnell's Mooch comics, although I'm sure I must have at some point. Either way, I was not familiar with the characters, nor does one need to be to appreciate this book and its message of friendship and simplicity. It is not an in-your-face message, just that companionship and love are things to cherish over material objects, and it certainly hit home with me.

The illustrations are line drawings in black ink with red accents, yet McDonnell captures expression and emotion with little decoration. The quality of the paper is important as well, and since it is recycled paper it has a greyish hue with tiny flecks of darker colour in it. It is also nice and thick and doesn't stick together like shiny paper can tend to do. The fact that the text appears only at the top of and is, at most, 2 lines per page allows the illustrations to convey humour and affection as needed.

While there is a definite message that The gift of nothing is getting across, it is one that is worthwhile told with artistry, humour and grace.

The little prince by Joann Sfar, adapted from the book by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Houghton Mifflin, 2010

A man is stranded in the desert with a broken-down airplane. He is asleep one night when the little prince awakes him with a request: "Please. Draw me a sheep." Thus begins a friendship between a human and a small alien boy who wants to return to his home planet and the flower that he loves.

Sfar's graphic adaptation of the classic book by de Saint-Exupéry is very faithful to the original text. True, the entirety of the text is not included, but many of the conversations, the planets that the little prince visits, and details like the drawings that the man does are the same. I haven't done a strict adaptation-to-original comparison, but a quick skim through de Saint-Exupéry's book indicates that the essence of his tale is contained in Sfar's work.

The little prince looks quite a bit different in Sfar's adaptation: he has huge eyes and a football-shaped head. The tousled blond hair and scarf remain the same, but Sfar's version of the little prince is more alien-looking than de Saint-Exupéry's. Of course, the little prince is an alien, and his appearance grew on me throughout the book and now I can hardly picture him otherwise.

Sfar's style of illustration is distinctive. There is an informal, almost sketch-like quality to his drawings, such as scribbles to indicate texture on the ground. I'm not sure if there is an actual straight line in the entire book, but the drawing are anything but haphazard. The angles Sfar uses, especially on the planets that the little prince visits, vary widely and give a sense of the space and atmosphere at each planet. I found his interpretations of the aliens and other characters strange and fascinating, especially the king on the first planet with his elephantine nose and the fox on Earth whose ears look identical to his fluffy tail. Admittedly, Sfar's style took a few pages for me to get used to, but I ended up really liking it.

While not a replacement for Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's work, Sfar's graphic novel adaptation of The little prince is a lovely introduction to or a lovely reminder of a timeless story that holds a spot in many hearts.

Stone Fox by John Reynolds GardinerScholastic, 1980Ten-year-old Willy and his grandfather run a small farm just outside Jackson, Wyoming. One day, Grandfather wouldn't get out of bed and wouldn't talk. Doc Smith insisted nothing was physically wrong with him but that he had given up, and neither Doc nor Willy knew why. For the next few months, Willy takes care of Grandfather and the farm with his beloved dog Searchlight by his side. When a tax collector shows up and insists that they pay him $500 or the farm will be taken away, Willy must figure out a way to get that money. A local sled race looks to be the best bet, and a very large gamble it is. I read a blog post on the first day of the Iditarod a few weeks ago, and this book was reviewed as a great example of a dog race story. I checked the elementary library and it was there, so I snatched it up and finally read it last night. The review I read was correct: this is a superb dog race story. But it is far more than a book simply about a dog race, as I hope my above synopsis indicates. Willy is a remarkably capable young boy who not only takes care of himself and his grandfather by cooking meals and tending the fire but harvests the potato crop, sells the potatoes, purchases provisions for the winter, and attends school, all of which he takes in stride. Granted, this book is set at an indeterminate point in the past - probably around the turn of the 20th century - when rural children had many responsibilities from a young age, but his determination and independence is no less impressive. The title of the book is taken from the name of Willy's main competitor in the dog race, a First Nations man of seemingly incalculable height who has never lost a race and never speaks. Although the word Indian is used to describe Stone Fox (likely due to the book being written 30 years ago), I appreciated the brief description of his use of his winnings to purchase land for displaced members of his Shoshone people to live on. The correlation between his motivation to win and Willy's motivation to win was not lost on either of them. Ah, Searchlight. Searchlight, Searchlight, Searchlight. Why do I keep reading books that make me want a dog? I don't have room, I'm not a fan of fur or drool, and vet bills would have me owing terrifying amounts of money to Visa. But geez, do I ever want a dog like Searchlight! She's so devoted to Willy that she waits for him all day outside his school and she adores racing home through the woods. I mean, who wouldn't want a dog that could haul you a few miles home while you rode a dog sled behind them? Going dog sledding is on my bucket list though, so perhaps it is just me. Gardiner packs a lot of heart into 81 pages. Great story, great characters (both human and dog), and great ending.

Dealing with Dragons (Enchanted Forest Chronicles - book 1) by Patricia C. WredeMagic Carpet Books (Harcourt), 1990Cimorene is the youngest of the King of Linderwall's seven daughters, and she hates being a princess. In order to avoid royal life and marrying a prince she considers dull, Cimorene volunteers to become a dragon's princess. Although traditionally princes save princesses who have been taken by dragons, Cimorene relishes the relative freedom and becomes caught up in a plot involving wizards, dragons, and a magic stone. Cimorene is a character that might result when the Paper Bag Princess got a little bit older: brave, smart, independent, and with no interest in being rescued by a prince. Cimorene is also perceptive and witty, and I liked her a lot (I imagine it would be quite difficult to dislike Cimorene). I found the vast majority of the characters to be entertaining and consistent, from Alianora to Kazul. Even Moranz was fun. In fact, the my entire experience with Dealing with dragons can be summed up with that word: fun. The plot was suitably thick, the wit was quick, new and unexpected characters were delightful, and I am very much looking forward to reading the rest of the series.

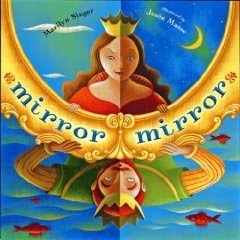

Mirror Mirror: a book of reversible verse by Marilyn Singer, illustrated by Josée MasseDutton Children's Books, 2010Fairy tales are told from two perspectives using the same poem, but read in reverse the second time. Deceptively simple premise, yes? Well, Marilyn Singer has come up with over a dozen pairs of poems that tell parts of fairy tales using the same words and the same lines, in a style she calls reverso. In her words: "When you read a reverso down, it is one poem. When you read it up, with changes allowed only in punctuation and capitalization it is a different poem" (last page of unpaginated book). Amazingly, it really works. I'm glad I read this book today for a second time, because when I read it for the first time last week I wasn't a huge fan of it: it struck me as gimmicky and some of the poems felt awkward. I must have been tired or in a foul mood because today I really enjoyed it. Admittedly, some of the poems don't flow as nicely as I would have liked, but when it clicks all is well in the world. My favourites of the 14 reverso pairs are The Doubtful Duckling and Longing for Beauty, both of which deal with the characters' emotions (the Ugly Duckling and Beauty and the Beast, respectively) as opposed to a description of events. In fact, the reversos in the book generally fall into one of those two categories: description of events and description of characters' feelings. Overall, I felt the ones that addressed emotions were more effective, but that may be my own bias. I must comment on the illustrations by Josée Masse because they are, in a word, spectacular. Each illustration is divided into two to reflect the reverso poems on the opposite page, and Masse creates beautiful links between each pair of illustrations. For example, Sleeping Beauty's skirt blends perfectly into the hills being climbed by the prince coming to save her. The illustrations are luminous, full of rich golds and greens and reds, and combine perfectly with the poems. For young students interested in poetry or fairy tales, this book will open their eyes to a challenging and fun style of writing.

Houdini: the handcuff king by Jason Lutes & Nick BertozziThe Centre for Cartoon Studies, 2007It is 5:00am on May 1, 1908, and Harry Houdini is preparing for a handcuffed jump off of Harvard Bridge in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He checks the police-issued handcuffs, goes for a jog, and reviews the stunt plan with the police and his assistant. With the river almost freezing over and a large crowd expected, Houdini has his livelihood as well as his life at stake. The handcuff king is from the same publisher as my earlier-reviewed Amelia Earhart: this broad ocean, and it bears some striking similarities. Three colours are used in the drawings - in this case black, white, and a grey-blue - and there is a lengthy introduction by Glen David Gold, who wrote a biography about one of Houdini's contemporaries. Also, at the end of the book, there are more than four pages that provide supplementary details about specific panels in the book, from how the locks of the early 20th century worked to promotion and advertising during that time period. In fact, the back matter provides the context needed for this very brief glimpse into Houdini's life. The entire book spans the events of one day , and one stunt, in Houdini's career. It is a snapshot of the man he was, from his adoration of his wife Bess to the control he had over every single aspect of a performance, and an indication of his ability to attract huge crowds to his spectacles. The illustrations were detailed, particularly the crowd scenes, although I found the lettering style distracting. My favourite part of the book was when Houdini is struggling to escape from the handcuffs while underwater, which is shown on the panels at the edge of each page, and the reactions of the crowd and the ticking clock is shown in inner panels. It gives a distinct atmosphere of concurrent events and certainly increased the tension of the moment for me, and I appreciate how the Lutes and Bertozzi take this life-threatening stunt that would be a memorable event in most people's lives, and present it as a common occurrence in Houdini's life. The handcuff king is an accessible introduction to the life of a man that holds mystique for many, and in a format that students will be drawn to and learn from.

Nasreen's secret school by Jeanette Winter

Beach Lane Books, 2009

Nasreen and her grandmother live alone in Herat, Afghanistan, after Nasreen's father was taken away by Taliban soldiers and her mother has disappeared in an attempt to locate him. It has been many months and Nasreen has not spoken since her father was taken. Although the Taliban does not allow girls to go to school, Nasreen's grandmother wants her to learn about the world as she had so she finds out about a secret school for girls and takes Nasreen. Although it takes many more months, with the help of a friend Nasreen moves past her parents' disappearances and begins to learn.

This is not a light storybook, and Jeannette Winter does an admirable job explaining the Taliban regime and its ramifications on the daily lives of women in a succinct and easily understood manner. The recent history of Afghanistan is very briefly summarized in the first couple of pages, enough to provide context to the story, especially that the Taliban was a new regime and made radical changes to society. The arrival of the Taliban is correlated with a dark cloud settling over the city, and that cloud is visible in the majority of the illustrations. The author's note at the beginning reveals that the Taliban fell in 2001 but that danger still remains, and that girls going to school is still not accepted practice.

Not wholly dark, apart from the cloud Winter's illustrations are generally quite bright and patterned. Nasreen always wears the same clothing which makes it easier to pick her out from the crowd of girls at her school, as do her green eyes, and the pinks, oranges, and greens Winter often uses are a welcome lift from the text.

The idea of having a parent taken away and another disappearing is undoubtedly a scary subject for young children, especially as the book is based on a true story. As well, while the story ends on a happy note, within the confines of the book news of Nasreen's parents is never found and the Taliban is still, presumably, in power. For children who balk at the idea of parents being taken away this could prove to be a bit much, and so I would caution adults to read this book before presenting it to young children.

Nasreen's secret school provides a perspective not often seen in picture books: children who need to avoid mortal danger simply to have the opportunity to learn. Although perhaps scary for some children, it is a book that ends with hope and a positive look to the future, and would be an excellent read-aloud to raise awareness of the continuing plight of women in Afghanistan for older children and teens as well.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed